Native American, Vintage Zia Poly Chrome Dough Bowl, Ca 1940's, #1447 SOLD

$ 2,329.00

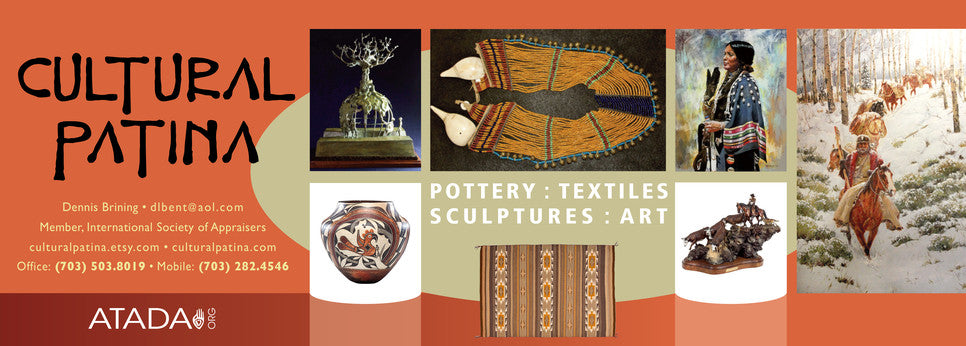

Native American, Vintage Zia Poly Chrome Dough Bowl, Ca 1940's, #1447

Description: #1447 Native American, Vintage Zia Poly Chrome Dough Bowl, Ca 1940's,

Dimensions: Height: 4 1/4'in, Diameter: 12'in

Condition: very good for age

Provenance: Ex-Bonhams, Estate of Michael Denman

Michael Denman was born in Portland, Oregon, in 1929. Like his brothers Peter and Denny, Michael graduated from the Lakeside School in Seattle. After attending the University of Washington and majoring in business, he joined the U.S. Air Force and became a B-47 pilot in the Strategic Air Command. While stationed in Arizona, he began an interest in Southwest and indigenous art that continued throughout his life. Following his time in the military, Mr. Denman moved to San Francisco and worked as a realtor for Hill & Co., a San Francisco real estate and property management company.

Reflecting his real estate acumen, entrepreneurial streak and sense of adventure, in 1984 he and a partner leased a 1950's bait shop and the boat repair yard next door. Ideally situated on the San Francisco waterfront, he envisioned the site's potential and possibilities, although at the time, the location was on the outskirts of town. Soon after, the bait shop became The Ramp, a popular locals' hangout for dining, drinking and dancing – considered to be a hidden gem by its diverse patrons. As Peter Denman says, it was begun as "a laid-back place where everyone of different stripes could come for a bite and a drink and relax" – a spirit that still continues.

Today however, as San Francisco's population grew and its footprint expanded, The Ramp's location in the Dogpatch has become one of

San Francisco's most desirable areas to live and work. Michael Denman's discerning eye wasn't only for real estate. Beginning in the 1970's, he also became an avid collector of many things that piqued his interest. Several areas were of particular appeal, often broadened by

family connections. Early on, he became a collector of Inuit works from Canada, specifically, from Cape Dorset and north of Hudson Bay. Mr. Denman became interested because Terry Ryan, the husband of his niece Leslie Boyd, launched Dorset Fine Arts in Toronto in

1978, as the wholesale marketing division of the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative in Cape Dorset, Nunavut. Representing many acclaimed sculptors and drawing artists, Dorset Fine Arts was established to develop and serve the market for Inuit fine art produced by the artist

members of the co-operative.

Likewise, his interest in the Southwest and Native America was inspired by the talents and enthusiasms of his great aunt, Leslie Van

Ness Denman, a prominent San Franciscan with deep roots in the city: her grandfather (and Michael's great-great-grandfather) James Van

Ness served as its seventh Mayor from 1855 to 1856. Mrs. Denman was very active in promoting the welfare and artistic talents of the

Navajo and Hopi tribes in the Southwest, encouraging artists in their work and identifying those who were superior. She served on the

Indian lore committee for the San Francisco International Exposition in the 1930's. She also wrote many pieces on Southwest arts for the

Grabhorn Press in San Francisco, which was the leading fine printing establishment in the U.S. from the early 1920's to the mid-1960's.

Inspired by his time in Arizona and his family relationships, Michael Denman began collecting Native American and Northern Canadian

works of art, sourcing items at auctions, galleries and dealers in the Southwestern U.S. and Canada. Propelled by curiosity and avid

reading, he continued to augment both the quantity and quality of the collection as his interest, fortunes and sophistication grew.

As his brother Peter says, "Michael had exceedingly good taste and a good eye, both for elegance and quality. Starting there, he began

his pursuit."

Michael Denman passed away in late 2018. The collection comes to auction now because of logistics: Peter, the heir to the estate, and his wife Susan live in Hawaii, and their children are not able to house the collection. It is for these reasons that others can now enjoy the fine acquisitions of indigenous cultures amassed by Michael Denman over 50 years.

Some background on Pueblo Pottery Making

“Pueblo pottery is made using a coiled technique that came into northern Arizona and New Mexico from the south, some 1500 years ago. In the four-corners region of the US, nineteen pueblos and villages have historically produced pottery. Although each of these pueblos use similar traditional methods of coiling, shaping, finishing and firing, the pottery from each is distinctive. Various clay's gathered from each pueblo’s local sources produce pottery colors that range from buff to earthy yellows, oranges, and reds, as well as black. Fired pots are sometimes left plain and other times decorated—most frequently with paint and occasionally with applique. Painted designs vary from pueblo to pueblo, yet share an ancient iconography based on abstract representations of clouds, rain, feathers, birds, plants, animals and other natural world features.

Tempering materials and paints, also from natural sources, contribute further to the distinctiveness of each pueblo’s pottery. Some paints are derived from plants, others from minerals. Before firing, potters in some pueblos apply a light colored slip to their pottery, which creates a bright background for painted designs or simply a lighter color plain ware vessel. Designs are painted on before firing, traditionally with a brush fashioned from yucca fiber.

Different combinations of paint color, clay color, and slips are characteristic of different pueblos. Among them are black on cream, black on buff, black on red, dark brown and dark red on white (as found in Zuni pottery), matte red on red, and poly chrome—a number of natural colors on one vessel (most typically associated with Hopi). Pueblo potters also produce un-decorated polished black ware, black on black ware, and carved red and carved black wares.

Making pueblo pottery is a time-consuming effort that includes gathering and preparing the clay, building and shaping the coiled pot, gathering plants to make the colored dyes, constructing yucca brushes, and, often, making a clay slip. While some Pueblo artists fire in kilns, most still fire in the traditional way in an outside fire pit, covering their vessels with large potsherds and dried sheep dung. Pottery is left to bake for many hours, producing a high-fired result.

Today, Pueblo potters continue to honor this centuries-old tradition of hand-coiled pottery production, yet value the need for contemporary artistic expression as well. They continue to improve their style, methods and designs, often combining traditional and contemporary techniques to create striking new works of art.” (Source: Museum of Northern Arizona)

Description: #1447 Native American, Vintage Zia Poly Chrome Dough Bowl, Ca 1940's,

Dimensions: Height: 4 1/4'in, Diameter: 12'in

Condition: very good for age

Provenance: Ex-Bonhams, Estate of Michael Denman

Michael Denman was born in Portland, Oregon, in 1929. Like his brothers Peter and Denny, Michael graduated from the Lakeside School in Seattle. After attending the University of Washington and majoring in business, he joined the U.S. Air Force and became a B-47 pilot in the Strategic Air Command. While stationed in Arizona, he began an interest in Southwest and indigenous art that continued throughout his life. Following his time in the military, Mr. Denman moved to San Francisco and worked as a realtor for Hill & Co., a San Francisco real estate and property management company.

Reflecting his real estate acumen, entrepreneurial streak and sense of adventure, in 1984 he and a partner leased a 1950's bait shop and the boat repair yard next door. Ideally situated on the San Francisco waterfront, he envisioned the site's potential and possibilities, although at the time, the location was on the outskirts of town. Soon after, the bait shop became The Ramp, a popular locals' hangout for dining, drinking and dancing – considered to be a hidden gem by its diverse patrons. As Peter Denman says, it was begun as "a laid-back place where everyone of different stripes could come for a bite and a drink and relax" – a spirit that still continues.

Today however, as San Francisco's population grew and its footprint expanded, The Ramp's location in the Dogpatch has become one of

San Francisco's most desirable areas to live and work. Michael Denman's discerning eye wasn't only for real estate. Beginning in the 1970's, he also became an avid collector of many things that piqued his interest. Several areas were of particular appeal, often broadened by

family connections. Early on, he became a collector of Inuit works from Canada, specifically, from Cape Dorset and north of Hudson Bay. Mr. Denman became interested because Terry Ryan, the husband of his niece Leslie Boyd, launched Dorset Fine Arts in Toronto in

1978, as the wholesale marketing division of the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative in Cape Dorset, Nunavut. Representing many acclaimed sculptors and drawing artists, Dorset Fine Arts was established to develop and serve the market for Inuit fine art produced by the artist

members of the co-operative.

Likewise, his interest in the Southwest and Native America was inspired by the talents and enthusiasms of his great aunt, Leslie Van

Ness Denman, a prominent San Franciscan with deep roots in the city: her grandfather (and Michael's great-great-grandfather) James Van

Ness served as its seventh Mayor from 1855 to 1856. Mrs. Denman was very active in promoting the welfare and artistic talents of the

Navajo and Hopi tribes in the Southwest, encouraging artists in their work and identifying those who were superior. She served on the

Indian lore committee for the San Francisco International Exposition in the 1930's. She also wrote many pieces on Southwest arts for the

Grabhorn Press in San Francisco, which was the leading fine printing establishment in the U.S. from the early 1920's to the mid-1960's.

Inspired by his time in Arizona and his family relationships, Michael Denman began collecting Native American and Northern Canadian

works of art, sourcing items at auctions, galleries and dealers in the Southwestern U.S. and Canada. Propelled by curiosity and avid

reading, he continued to augment both the quantity and quality of the collection as his interest, fortunes and sophistication grew.

As his brother Peter says, "Michael had exceedingly good taste and a good eye, both for elegance and quality. Starting there, he began

his pursuit."

Michael Denman passed away in late 2018. The collection comes to auction now because of logistics: Peter, the heir to the estate, and his wife Susan live in Hawaii, and their children are not able to house the collection. It is for these reasons that others can now enjoy the fine acquisitions of indigenous cultures amassed by Michael Denman over 50 years.

Some background on Pueblo Pottery Making

“Pueblo pottery is made using a coiled technique that came into northern Arizona and New Mexico from the south, some 1500 years ago. In the four-corners region of the US, nineteen pueblos and villages have historically produced pottery. Although each of these pueblos use similar traditional methods of coiling, shaping, finishing and firing, the pottery from each is distinctive. Various clay's gathered from each pueblo’s local sources produce pottery colors that range from buff to earthy yellows, oranges, and reds, as well as black. Fired pots are sometimes left plain and other times decorated—most frequently with paint and occasionally with applique. Painted designs vary from pueblo to pueblo, yet share an ancient iconography based on abstract representations of clouds, rain, feathers, birds, plants, animals and other natural world features.

Tempering materials and paints, also from natural sources, contribute further to the distinctiveness of each pueblo’s pottery. Some paints are derived from plants, others from minerals. Before firing, potters in some pueblos apply a light colored slip to their pottery, which creates a bright background for painted designs or simply a lighter color plain ware vessel. Designs are painted on before firing, traditionally with a brush fashioned from yucca fiber.

Different combinations of paint color, clay color, and slips are characteristic of different pueblos. Among them are black on cream, black on buff, black on red, dark brown and dark red on white (as found in Zuni pottery), matte red on red, and poly chrome—a number of natural colors on one vessel (most typically associated with Hopi). Pueblo potters also produce un-decorated polished black ware, black on black ware, and carved red and carved black wares.

Making pueblo pottery is a time-consuming effort that includes gathering and preparing the clay, building and shaping the coiled pot, gathering plants to make the colored dyes, constructing yucca brushes, and, often, making a clay slip. While some Pueblo artists fire in kilns, most still fire in the traditional way in an outside fire pit, covering their vessels with large potsherds and dried sheep dung. Pottery is left to bake for many hours, producing a high-fired result.

Today, Pueblo potters continue to honor this centuries-old tradition of hand-coiled pottery production, yet value the need for contemporary artistic expression as well. They continue to improve their style, methods and designs, often combining traditional and contemporary techniques to create striking new works of art.” (Source: Museum of Northern Arizona)

Related Products

Sold out

Sold out