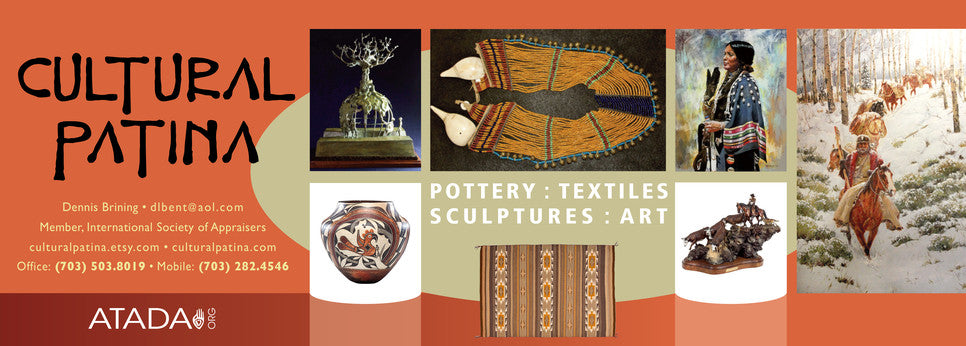

Outstanding Native American, Large Navajo weaving, Tree of Life, Ca 20th Century, #1132-Sold

$ 2,625.00

Extraordinary Native American, Large Navajo weaving, Tree of Life, Ca 20th Century, #1132

Description: #1132 Extraordinary Native American, Large Navajo weaving, Tree of Life, Ca 20th Century, 20th C.

Dimensions:: 50" x 32" Approx Weight: 3.25 Lbs.

Condition: Excellent like new condition.

Some Tree of Life Navajo Rug background notes:

Posted on November 30, 2015 by Jason

From the beginning of recorded history man has revered trees as sacred symbols of creation, fertility, resurrection and immortality. With roots firmly planted in the earth, sturdy trunks and branches reaching to the sky, trees were believed to connect the three realms of existence: underworld, terrestrial and celestial. Since the days of Mesopotamia trees such as the palm, ash, beech, oak and pine have been viewed as ladders leading from the unconscious to enlightenment, sheltering canopies for all of creation, shamanic routes to knowledge and pillars between heaven and earth. The Tree of Life Navajo Rug, or Cosmic Tree, is associated with the sacred feminine, with springs, vegetation and life giving waters.

For the Navajo, a race which migrated in ancient days from the wooded forests of Siberia to the dry desert lands of the American southwest, a new “tree” took hold as their world axis – Corn.

The “Holy Ones told the Navajos in the beginning, Corn will be your food, your prayer. Corn, the Navajo tree of life, was given to the Diné at creation as a gift…” (Capelin:2009)

For the Navajo corn is everything. In their origin myth they were created from corn.

“White Body carried two ears of corn, one yellow, one white…” The ears were placed between sacred buckskins with their tips facing east. “The white wind blew from the East and the yellow wind blew from the West, between the skins.” When “the upper buckskin was lifted; the ears of corn had disappeared.” The ear of white corn had become First Man and the yellow ear, First Woman. (Locke:2010)

Corn is holy, divine. Corn is life giving nourishment to man and animal. Corn is utilized in every way by the Navajo and most importantly, corn holds the promise of life in its wafting grains of pollen.

The Tree of Life Navajo rug design first appeared in the late 1800's. “When the Navajo weavers started to weave pictorial rugs, they also started to manufacture rugs which depicted yei (Holy People) and cornstalks…the oldest wall hangings and rugs show a type of design that alternates yei and cornstalks, almost always with a bird on their tips or portrays Corn People as cornstalks with Yei heads with birds perched on the leaves.” (Busatta:2013)

Contemporary Navajo Tree of Life rugs usually depict an upright cornstalk growing from a Navajo Wedding basket, the sacred basket whose center represents the Navajo point of emergence. The cornstalk’s green leaves shelter and support birds and creatures from the animal kingdom. The Navajo walk in balance and inter-connectedness with all beings. “We learned our songs from the birds,” an elder medicine man said. “We learned our music, our voices, from the birds.” The yellow tassels at the top of the cornstalk represent sacred pollen. Corn pollen is prayer to the Navajo. “You put some in your mouth for your voice,” the elder said, “the voice you speak. Then you put some on the top of your head for the oxygen that has come into you. And then you sprinkle the corn pollen forward, where you want to go. In the old days we used to pray with corn pollen that had been dusted on the tail of a bluebird. That was high medicine.” Corn pollen is also seen as light, luminosity. “The pollen at the tassel tip is hit by the sun – ZAP! – like lightning,” the medicine man said.

The cornstalk in a Tree of Life Navajo rug can also be viewed as a metaphor for man’s birth and development. Corn is man and man is corn. The holy Corn People represent our highest selves. The ear is man’s “fruit” in life, his accomplishment and maturation. Pollen is man’s spiritual illumination. For the Navajo “the cornstalk’s process of life is a metaphor, like a ladder, and as humans develop and grow, they attain levels and grades in degree of teaching, learning and understanding.” In order to reach pollen’s radiance and purity one must follow the wisdom path.

When asked a final time about the meaning of the Tree of Life design, the medicine man said, “It’s the root, four; four stages of life, four elements, four directions. It’s harmony within the harmony. Underneath it all is First Woman, the lady from the North. It’s ‘looking back in.’ Corn is Grandmother, Grandfather. Walking under the corn leaf is the Beauty Way. We call it, iiná, Life.” (Source: Perry Null Trading Company)

A Brief Social History of Navajo Weaving and a bit of historical context for a popular contemporary collectible

There is an ageless beauty to Navajo weaving. Navajo weaving's are many things to people. Above all else, Navajo weaving's are masterworks, regardless of whose criteria of art is used to judge them. They are evocative, timeless portraits which, like all good art, transcend time and space. Navajo weaving has captured the imagination of many not only because they are beautiful, well-woven textiles but also because they so accurately mirror the social and economic history of Navajo people. Succinctly, Navajo women wove their life experiences into the pieces.

Navajo people tell us they learned to weave from Spider Woman and that the first loom was of sky and earth cords, with weaving tools of sunlight, lightning, white shell, and crystal. Anthropologists speculate Navajos learned to weave from Pueblo people by 1650. There is little doubt Pueblo weaving was already influenced by the Spanish by the time they shared their weaving skills with Navajo people. Spanish influence includes the substitution of wool for cotton, the introduction of indigo (blue) dye, and simple stripe patterning. Besides the "manta" (a wider-than-long wearing blanket), Navajo weavers also made a tunic-like dress, belts, garters, hair ties, men's shirts, breech cloths, and a "serape-style" wearing blanket. These blankets were longer-than-wide and were patterned in brown, blue and white stripes and terraced lines.

For more than a century, the products of Navajo looms were probably identical to those of their Pueblo teachers, but by the end of the 1700s Navajo weaving began its divergence. While Pueblo weavers remained conservative, Navajo weavers learned that wefts did not need to be passed through all the warps each time, but rather, by stopping at whatever point they wished they could create patterning other than horizontal bands. These "pauses" in Navajo weaving are often seen as "lazy-lines" (diagonal lines across the horizontal wefts) in finished pieces. By 1800, weavers were using this technique to create terraced lines and discrete design elements. Navajo weavers also demonstrated more willingness to use color than their Pueblo teachers.

Spanish documents describing the Southwest in the early 18th century mention Navajo weaving skills. By the 1700's Navajo weaving was an important trade item to the Pueblos and Plains Indian people. In 1844, Santa Fe Trail traveler Josiah Gregg reported, "a singular species of blanket, known as the Serape Navajo which is of so close and dense a texture that it will frequently hold water almost equal to gum-elastic cloth. It is therefore highly prized for protection against the rains. Some of the finer qualities are often sold among the Mexicans as high as fifty or sixty dollars each."

Blankets were traded great distances as evidenced by their appearance in Karl Bodmer's 1833 painting of a Piegan Blackfoot man (Montana) wearing what appears to be a first-phase Chief's blanket or an 1845 sketch of Cheyenne at Bent's Fort (Colorado) wearing striped blankets. Historic photographs illustrate that the desirability of blankets increased with the 19th century. Closer and more frequent trading partners included the Utes, Apaches, Comanche’s, and Pueblos.

The Spanish or Mexicans had never been able to reach a lasting peace with the Navajo. When Mexico ceded the Southwest to the United States in 1848, the "Navajo Problem" was also inherited. With a pronounced resolve, Kit Carson led a "Scorched Earth" campaign in 1863–4, destroying food caches, herds and orchards, ending in 8000 Navajo people surrendering. They were marched hundreds of miles to an arid, barren reservation, Bosque Redondo, at Fort Sumner in eastern NM.

For five years the people endured incarceration with shortages of supplies, food, and water. Their culture changed dramatically during this period, not least in weaving. To substitute for their lost flocks, annuities were paid which included cotton string, commercially-manufactured natural- and aniline-dyed yarns as well as manufactured cloth and blankets. These lessened the Navajo people's reliance on their own loom products. In 1867, four thousand Spanish-made blankets were distributed to the Navajos as part of their annuity payment. The combination of widespread availability of yarns and cloth and the influence of the Spanish Saltillo designs were probably a direct inspiration in the dramatic shift in weaving during the Bosque Redondo years, from the stripes and terraced patterns of the Classic period to the serrate or diamond style of the Transitional period. It is testimony to the resiliency of Navajo culture that a period of internment could produce a robust period of change and continuity in weaving.

In 1868, the Navajo were allowed to return to their beloved mesas and canyons. In exchange for their return they promised to cease aggression against neighboring peoples, and to settle and become farmers. Reservation life brought further dramatic changes to Navajo culture, including a growing reliance on American civilization and its products. The sale of weaving's in the next thirty years would provide an essential vehicle for economic change from barter to cash. Annuity goods included yarns, wool cards, indigo dye, aniline dyes, and various kinds of factory woven cloth. Skirts and blouses made of manufactured cloth replaced the woven two-piece blanket dress. Manufactured Pendleton blankets displaced hand-woven mantas and shoulder blankets so that by the 1890's, there was relatively little need for loom products in Navajo society.

US government-licensed traders began to establish themselves on the new Navajo Reservation. Whatever their motivation, adventure or commerce, the traders became the chief link between the Navajo and the non-Indian world.

Trading posts exchanged goods for Navajo products such as piñon nuts, wool, sheep, jewelry, baskets, and rugs. While wool and sheep were important to Navajo people for weaving and meat, they were also important to the economy beyond the Reservation. Wool was in great demand in the industrialized eastern US for coats, upholstery, and other products. Traders bought wool by the pound and sold it to wool brokers in Albuquerque and Las Vegas, New Mexico. The sheep purchased by traders were herded to the nearest rail head and on to the slaughterhouses. The herds grew substantially and it became more profitable for Navajo people to sell wool rather than utilize it in weaving.

The railroad reached Gallup, NM in 1882, establishing a tangible connection between the Navajos and the wider market, with the traders acting as middlemen. The completion of the railroad signaled the closing of the American Frontier which, in turn, stimulated a nationwide interest in collecting American Indian art. The railroad made travel to the vast reaches of the west easier and thus opened the area for tourists. The traders recognized these new markets and began to influence weaving by paying better prices for weaving's they thought more attractive to non-Indian buyers. This new market, coupled with the Navajo's decline in use of their hand woven products, infused new life into Navajo textile arts.

By the 1880s, trading posts were well established on the Navajo Reservation, and traders encouraged weaving of floor rugs and patterns using more muted colors which they thought would appeal to the non-Indian market. By 1920, many regional styles of Navajo weaving developed around trading posts. These rugs are often known by the area's trading post's name.

The history of Navajo weaving continues; over the past century, Navajo weaving has flourished, maintaining its importance as a vital native art to the present day. Virtually all the nineteenth and twentieth-century styles of blankets and rugs are still woven, and new styles continue to appear.

________________________________________

Thanks to Bruce Bernstein, former director, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Museum of New Mexico, Santa Fe

originally appeared in The Collector’s Guide to Santa Fe and Taos - Volume 11