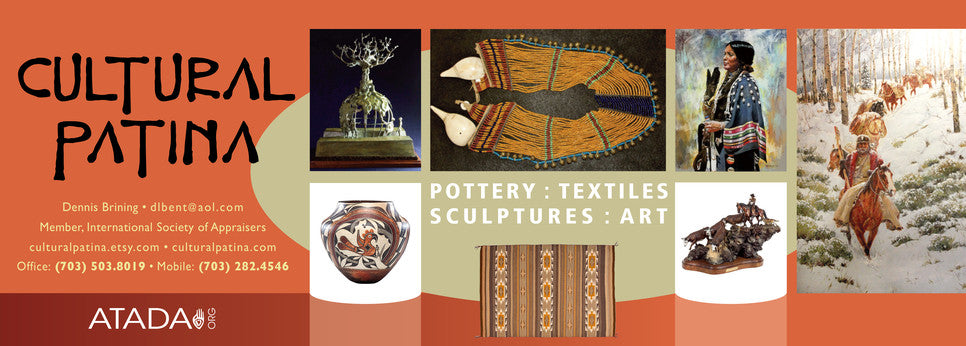

Native American, Chemehuevi Tray, Ca 1920-30, #1028 SOLD

$ 3,750.00

1027: Description: Native American, Chemehuevi Tray, Ca 1920-30,

Provenance: and came from Margaret Taylor Estate: Margaret Taylor was a teacher for many years near the Hopi and Navajo reservations around Flagstaff, Arizona. She greatly enjoyed meeting weavers and purchasing their wares, thereby helping support their families. A collector for decades, she filled her home with baskets, rugs and other items, adorning it throughout with items on display from her collection. Items offered in this auction – mostly contemporary and post-World War II works – include Navajo and Hopi basketry, rugs, jewelry and pottery. This collection showcases the width and breadth of recent Hopi and Navajo art, stretching its design vocabulary, and reinforcing that this is not a dying art, but one that is vibrant and alive.

Dimensions: 11.5 inches diameter, 2.5 inches high.

Condition: Very good for age. Has small nail hole in the bottom, and a light spot of dirt along the side.

Some back ground on the Chemehuevi Indians

THE CHEMEHUEVI INDIAN TRIBE:

Nüw (The People) were very civilized, not prone to human or animal sacrifice. All things, particularly those in nature, were revered as gifts from the Creator, the Ocean Woman. All Her creatures and even inanimate objects were endowed with supernatural powers, particularly the Animals (The First People). Mouse and Wood rat, for example, were able to extract diseases from a person.

There were three ages of Nüw civilization though some non-Indian “experts” say there were two. When the Earth Was Covered with Water speaks of Creation, When the Animals Were People was the time of myth and magic, and When Wolf & Coyote Went Away began the age of man. In story-telling, a winter pastime, one always precedes his story with the appropriate phrase.

After Wolf & Coyote Went Away, man was on his own. The Creator’s two helpers left us with everything we needed to survive and rose to the sky to become the rainbow. Their colorful capes drape the earth after a rain.

Religion was in no way ritualistic but more a personal and individual relationship between a person and the Creator. The gods are called Huivarum Karur, which means “those who sit here” and, when said, the space beside one is always indicated. It was not until modern times that Chemehuevi accepted the Christian notion that the Creator was male and became known as a “he”. Prayers were said only to the Ocean Woman in times of trouble. When a child lost its first baby tooth, the tooth was thrown away with a prayer to Her that she replace it with a bigger and better one. Prayers to the departed (Spirits) were necessary to protect the living, especially children. Religion and daily living were one and the same, so no aspect of life was dichotomized.

Our nomadic forebears traveled in family groups and very often settled near relatives and became a virtual village. Chieftainancy was inherited, handed down from father to the eldest son, and these Clan Chiefs were outranked by the High Chiefs, who were revered almost as much as the shamans. Black- eyed beans were said to be the food of the High Chiefs as its properties gave them wisdom and courage.

Male and female children were treated the same. All learned to make weapons and tools, and hunt and prepare food because survival skills were paramount. As they neared puberty, they would begin to learn the differences between men and women, which, to the old ones, were few. The roles of men and women were never defined or delineated because both had to do the same kind of work at some point. While parents were initially responsible for them, it was incumbent on sundry aunts and uncles to keep children in check; “it takes a village” certainly applied then.

The sense of right and wrong began at an early age and usually came from stories (fables, if you will). Bad behavior invited unbearable gossip and public ridicule. The most extreme punishments were banishment or death. Death was perhaps the more preferred because a banished person could never return or claim to be of the people who had driven him away. As in a death, his name could never be spoken again. He finished out his days as a non- person.

Harmony and respect were the way. A person with negative traits such as anger, meanness of spirit, jealousy and laziness was considered a liability. Having a good sense of humor was very important to Nüw.

While much of the culture is lost, a few remember the stories and language of their forebears. The Chemehuevi Tribe offers classes in Nüwü Ampagap (the People’s Language). Nüw being a Southern Paiute, our language very closely resembles that spoken by the Moapa Paiutes. It is classified as Uto-Aztecan, and more precisely Numic.

Interesting “tidbits”

When a female infant’s umbilical cord falls off, it is put in Packrat’s nest so that she will be a good gatherer. A male infant’s is buried along a Deer trail so that he will be a good hunter.

It is customary to offer the first bite to the Spirits when you eat outdoors because you are in their domain.

Nüw did not eat anything from the water because it was thought unclean. It is likely that this goes back to the Creator.

When the Animals Were People, they gathered to discuss civilization. When it was time to decide how many seasons there should be, only Owl answered by raising a foot, so the number of seasons is four.

Material Culture, Technology

The material culture developed by the Chemehuevi is very much like that of their neighbors, the Mojave, Serrano, and Cahuilla. As is usually the case, apparent differences are in part due to the types of material that were available and in part to their preferences.

The Chemehuevi women were skilled basket makers, but made little pottery. Their coiled baskets resembled those of the San Joaquin Valley rather than those of southern California, often having constricted necks. Caps, triangular trays, and carrying baskets were diagonally twined. They usually painted designs on the baskets, rather than weaving them into the basket. Their coiled baskets were very distinctive because they were produced almost exclusively with split, peeled willow and black devil's claw on a two or three willow rod foundation that coils clockwise. The designs were occasionally painted on instead of weaving them into the baskets.

They made a self-bow shorter than that of the Mojave, with recurved ends, the back painted, and the middle wrapped. Arrows were often made of cane, and sometimes willow, with a foreshaft and a flint point. Houses were shelters against the wind and sun (Kroeber 1925:597-598; Laird 1976:5). The bow used in war was sinew-backed hickory, which was very hard to draw. It was short and powerful. Another kind of bow was made of the antler of the mule deer (Laird 1976:240).

Bows for hunting were made of sinew-backed willow. The adoption of the sinew-backed bow permitted the Chemehuevi to hunt big game, thus improving their supply of protein food (Laird 1976:5-6).

The principle material used for houses was brush. Of the four different kinds of houses they made, one was the flat or shade house, built for ceremonial occasions. A flat roof of brush was laid across four notched posts. Another roof that sloped to the ground on the west side was built above the flat roof to provide extra protection from the sun. In addition, a very large flat house was built to hold the goods brought to a Cry to be burned or given away (Laird 1976:42-43). Source: majavedesert.net